This biography was authored by Rusty Russell and has been extracted from Mast High Over Rotterdam – Please respect Rusty’s Copyright to the work as detailed in the first section of the book.

I should have met Ben Nunn at the very start of my research, rather than at the end, and all because of a slip-up with his rank at the time of the Rotterdam raid. On our first visit to the Public Record Office at Kew, my wife had correctly copied down Ben’s rank – sergeant – from the 21 Squadron ORB. When I transcribed her notes into my records, I must have assumed that it was an all-officer crew and ‘promoted’ Ben to pilot officer several months earlier than the notification appeared in the London Gazette!

As Ben was obviously not in the Air Force List in July 1941, I assumed that he was a Commonwealth officer; naturally, all my enquiries in this direction came to nought. The years passed by, and I reluctantly conceded that he would be one of the very few participants of the Rotterdam raid who would remain unidentified.

The breakthrough came in early 1990, when I was perusing my wife’s original notes. I could hardly believe my eyes when I read ‘Sgt Nunn’. It was too late for recriminations: action was required, and fast. Armed with information gleaned from London Gazettes (dates of commissioning), Air Force Lists (category of WOp/AG), and the 21 Squadron ORB (approximate dates of arrival and departure), I drew up a short list of highly probables, placing A.B.C. Nunn at the top. I wrote to the Records Office at Gloucester: were any of these gentlemen on 21 Squadron on 16th July 1941?

Rules, regulations and red tape made this task harder and longer than I would have hoped; but my patience was rewarded, and after several; frustrating replies, it was finally confirmed in November of that year that A.B.C. Nunn was, in fact, my man. Hallelujah!

The same day, I visited the Bodleian Library and settled down for a marathon session with the entire collection of telephone directories for the British Isles. Just three volumes from the end, and by then somewhat deflated, I found the entry I was looking for. Even better, the address was only in the next county!

A surprised Ben Nunn received a phone call from me that night, and, wasting no time, we agreed to meet just two days later – on Sunday 18th November. It was a good omen, being the 30th anniversary of my being awarded my RAF wings.

I met Ben in his delightful Gloucestershire home. Knowing that he was 76 years of age, and that he had retired from the RAF on medical grounds, I was somewhat bowled over by the sprightly, youthful gentleman who greeted me at the door. The long-overdue interview was at last to begin…

Many of the biographies, which it has been my privilege to compile, have left me feeling sad. Ben’s is not in this category: he freely admits that he is one of the luckiest to have emerged from the Second World War. Ben’s three brothers all served in the Forces and survived; his five sisters all had husbands who served in the Forces, and they too survived. Almost unique, I would think.

Ben was born in Aldershot on 24th May 1914, while his father was serving there. His early school years were spent at a little private school in Aldershot, after which he attended an elementary school in Queens Road, Farnborough. Ben was obliged to terminate his education at the age of 14; with his father dying at the young age of 46, he and his elder brother were suddenly needed to earn money for the large family.

Ben’s first job was as a warehouseman for the military printers, Gale & Polden, in Aldershot (Air Chief Marshal Sir David Lee GBE CB was a customer of this firm in 1933. Then a pilot officer, he ordered 100 visiting cards – Never Stop the Engine when it’s Hot: Thomas Harmsworth Publishing, 1983: David Lee). But low wages forced him to leave. His next employment was as a milkman. The rumblings of war were gathering momentum, and Ben pleaded with his mother as soon as he was of age, and again, with feeling, after Chamberlain’s Munich visit, to be allowed to join up. He reasoned that by doing so, he would get the service of his choice – the RAF – and thus avoid the possibility of being allocated elsewhere. His request could not be granted: the role of ‘bread-winner’ could not be relinquished until a younger brother was in a position to take over.

Membership of the Territorial Army, however, was permitted, and Ben joined the West Surreys at the age of 17, saying that he was one year older. His four years as a signaller in the TA meant that he was well versed in the Morse code before joining the RAF. Finally, on 21st July 1939, Ben was released from his family commitments and enlisted in the RAF. With his signalling background, the Air Ministry naturally put him into the wireless trade (ground). Ben recalls:

‘I didn’t even think of being aircrew at that time. So we were packed off to West Drayton; we were given our shilling [5p] – our signing-on shilling – and then we went off to Cardington. While at Cardington, war was declared, and it was then that I decided that I would like to be aircrew; as a result, I was posted to Yatesbury.’

Ben completed the WOp’s course at No 2 E&WS at the end of April 1940, and was then posted to RAF Station Odiham. ‘I was there’, Ben explains, ‘just bashing a key on a beacon, until the course came up at Jurby.’

After four weeks at No 5 B&GS Jurby, Isle of Man, Ben was the proud possessor of not only the wireless badge but also the air-gunner’s brevet. But no stripes yet: they would come later when he was stationed at Upwood.

Ben found himself, due to circumstances outside his control, on the ‘long course’ at 17 OTU, Upwood, and was there for nearly a full year. The problem was that every time he landed from a flight, he had suffered a painful nose-bleed. Ben was understandably fearful that this condition might mean the end of his flying career, but the RAF were not prepared to lose aircrew that easily and promptly despatched him to Ely Hospital for an operation at the end of February 1941. The operation was a gory one, and not for the faint-hearted. The sinus area was attacked with an instrument passed up Ben’s nose, and his antrums were punctured. ‘You just hear the crack’, Ben recalls, ‘and they drill it, and I was fine after that!’ Oo-er!

Nearly two months later, he was back on the flying programme at Upwood. On 4th May he crewed up with Freddie Reiss and Edmund Shewell. Leave was booked for ten days commencing 10th May, so that he could get married: the wedding arrangements had had to be brought forward a week due to ‘contingences of the service’. But there was more to come, as Ben recalls:

‘I said to Vera that I would be home at a certain time on 9th May, and we were flying right up until 8 or 9 o’clock of that night, which I wasn’t expecting, but had to go. I was just going out of the gate, and I was called back to the guardroom; and they said: “You’ve got 48 hours! Your ten days leave is cancelled!”

I got down to London very late, and had to spend the night on a seat on Waterloo Station, and catch the next morning’s milk train down to Farnborough.’

That night, London was bombed yet again. Vera continues the saga:

‘We were getting married the next day – a Saturday – and in the early hours of that day there was a knock at the door (my parents’ house). And it was a policeman, who said: “Are you friends of Sergeant Nunn?” I said: “Yes!” He said: “Well, he’s been delayed, but he hopes to get down in the morning”. All I could do was hope the bridegroom arrived in time!’

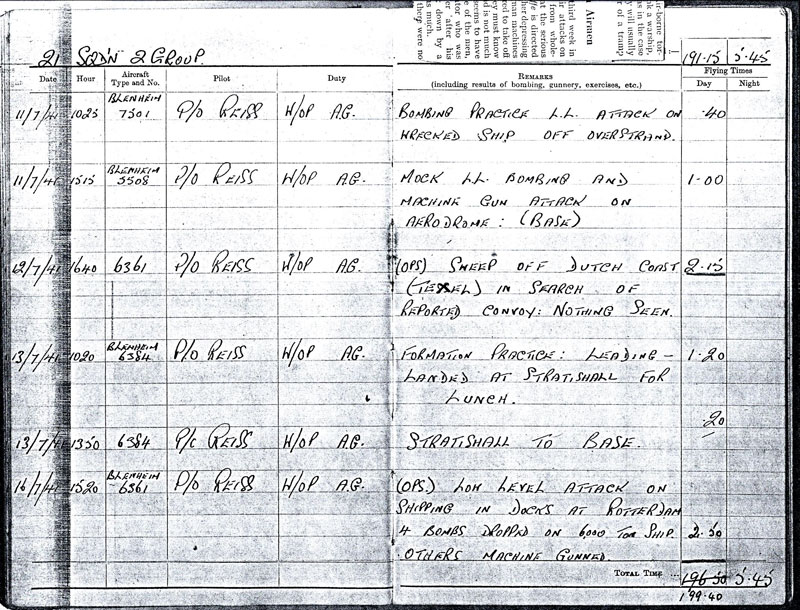

Ben and his crew were no doubt urgently required in 2 Group to replace the horrendous losses of that period, hence the RAF’s seemingly callous attitude. The crew joined 21 Squadron, during their detachment to Lossiemouth, on 9th June. It was a warm-up period, and their first operation, on 16th June, was completed after the squadron had returned to Watton. As so often happened, it was a case of being thrown in at the deep end. Ben’s entry in his logbook reads: ‘Sweep off Nordeney. Attacked ship (“Nautilus”). Near miss. Attacked by two Me 109F for 30 mins. Damaged one. Crash landed S. Bridge. (Day) 4.50’. On the page is pasted the photograph of Sgt Leavers’s last moments after he had lost a chunk of wing on the mast of the target vessel, and at the instant of passing 90º of bank before crashing. Ben’s observer, Edmund Shewell, took this photograph, which was used for propaganda purposes minus the evidence of Sgt Leavers’s demise.

Understandably, the day made an impression on Ben. He recalls:

‘I shall never forget my first raid. When we were attacked on the way back by two 109s for about 30 minutes, we were hit; and, in fact, Vera has still got one of the bullets that I took out of the TR9 set…It was quiet on the way back, all low level as you know; we were flying only a few feet from the sea. I got stuck into my rations, which included chocolate, when suddenly I saw a shower of bullets hitting the water; then I saw this 109 flash past and up in a steep climb. Quickly getting back onto the guns, I was able to fire only a few rounds before my guns jammed; so all I could do was point my guns at these 109s as they came down. One of them realised my predicament and brazenly flew alongside: we just looked at each other! We didn’t know, of course, that our hydraulics had been damaged, and we had to belly-flop at Sutton Bridge. Looking back on this day, I clearly recall what a sticky mess can result when one’s attention is on more-pressing matters than eating a bar of chocolate: it seemed to get everywhere.’

Sqn Ldr Tim Partridge landed at Sutton Bridge shortly afterwards to collect the crew, and flew them back to Watton in V6240 (my cousin’s aircraft on the Rotterdam raid).

Then began the familiar round of anti-shipping ‘beats’, high-level Circus operations against continental ‘fringe’ targets, all interspersed with bombing and formation practice.

On 10th July, Ben’s logbook reads: ‘Attacked shipping in docks at Cherbourg at low level. Tail unit damaged by hitting a breakwater…’ On the Rotterdam raid of 16th July, Ben gave his Leica camera to his observer, who had already established a reputation as a photographer, and opted to give his full attention to his twin Brownings, machine-gunning ships alongside the 6,000-tonner his pilot, Freddie Reiss, attacked with 4 x 250-pounders. His memories of this raid include seeing a Blenheim (my cousin’s aircraft) crashing into Waalhaven and a crane hawser that had been cut by the wing of another Blenheim, following which a suspended vehicle had dropped onto the deck of the ship! This was clearly the work of Sgt Wotherspoon (see his biography). On 23rd July, during an attack on shipping off Ostend, the crew were attacked by a Bf 109 for ten minutes. ‘Hits scored: believed a probable’, Ben recorded. (See Gilbert Lowes’s account of his last flight on this day). The Intelligence Officer confirmed that Ben was the only NCO to return from this costly raid.

‘How did you feel about the anti-shipping campaign of the Blenheim?’, I asked Ben. ‘Did you enjoy it?’ ‘No! I don’t think so!’, he replied, laughing. ‘I was scared stiff each time! I shall never forget one chap, who was on our squadron, an air-gunner; we were all getting ready to go off, and were testing out guns – firing then into the ground. And I noticed him getting out of the aircraft and he went back to the crewroom and said: “I’ve had enough!” You just couldn’t blame anybody for that, really. You didn’t know whether you were going to come back or what was going to happen. And there were many of them like that…’

Ben mentioned a couple of modifications to the Blenheim of which I was unaware. The first concerns a ‘screamer’ device. He explains:

‘Our squadron was used for testing out things. I remember particularly the “screamer”, you know, the whistle that you blow and it spins, and makes a screeching noise [a tit-for-tat vis-à-vis the Ju.87 Stuka?]. We had those actually fitted to try them out; about that size [two feet or so in diameter]. I don’t think that they were persevered with for very long.’

The other mod may have been set in motion by Ben. After a bullet had put the TR9 intercom out of action on his first operation, Ben said to Freddie Reiss:

‘What we want, because we don’t want to be in that position again, is a couple of flashlights or bulbs in front of you, one red and one green; and then, if the intercom goes, I’ve only got to press a button for starboard or port, for you to take evasive action.’ It was incorporated.

On 23rd August 1941, Ben and his crew set off for Portreath, in Cornwall, on the first stage of their posting to Nakuru, Kenya. Four days later, the 7½-hour slog to Gibraltar was completed. ‘9 Me 109F machines sighted off French coast. No trouble’, Ben recorded in his logbook. But Gibraltar to Malta proved a stumbling block. The first attempt, on 28th August, had to be thrown away after an hour, due to magneto trouble. The next attempt, two days later, was aborted for a different reason; Ben’s logbook records: ‘Sole accompanying machine crashed into sea owing to engine failure. Sent SOS message to Gib. Crew rescued by Catalina and corvette. Flight abandoned. Returned to Gib’. The next day, a further attempt was made, and again aborted, this time because of petrol tank trouble. Finally, on 2nd September, the marathon 8¼-hour sortie was successfully completed; an Italian seaplane was sighted near Pantelleria Island, but it caused no trouble.

For a Blenheim crew in transit to the Middle East, or Africa, the most dangerous part of the journey was the stop-over at Malta. The AOC, AVM Hugh Pugh Lloyd, had a habit of using such crews to replenish his rapidly depleting stocks, and the name of the game was to shoot through the island as quickly as possible. This very month, September 1941, witnessed the hijacking of Sgt Ivor Broom (later Air Marshal Sir Ivor Broom KCB CBE DSO DFC & 2 Bars AFC). I have adopted the word preferred by Sir Ivor Broom. In Briefed To Attack (Hodder & Stoughton 1949) Air Marshal Sir Hugh Lloyd admits to wangling, conceding that ‘this sharp practice gave Malta a bad name in the Middle East’!

Ben very nearly condemned his crew to a short career attacking Rommel’s convoys. He explains:

‘When I woke up in the morning, having stayed the night, I couldn’t open my eyes. I’d been bitten by sandflies. I didn’t even know what the time was, or anything. I just called out to somebody to lead me off to sick bay, to see if they could do anything. And they just got my eyes enough open to be able to see a little bit. And Freddie Reiss came in and said: “We’re not stopping here, Ben! We’re off!” Of course, we went! And having got up to about, I suppose, 20,000 feet, it was cool, and the swelling went down. I was all right by the time I got to Cairo.’

The crew handed over their Blenheim and flew by Imperial Airways Sunderland flying boat down to Nakuru, to join the staff of the newly-formed No 70 OTU.

On the last day of the year, Ben was commissioned. In April 1942, he was posted to 244 Squadron, Sharjah, arriving in an aircraft which did not impress him too much – a Vickers Valentia. He recalls:

‘We had to go down to Sharjah and pitch tents, and start a camp going, and try and stop enemy subs entering the [Persian] Gulf. [A theatre of war which is topical at the time of writing]. We also had a net across the Gulf underwater to stop these submarines…Awful nights there, you know, because you couldn’t sleep: it was so humid. And the aircraft used to get terribly hot. Our sole operations were concentrated on trying to stop the subs getting into the Gulf by using depth charges.’

Sharjah evokes a host of memories for Ben. First and foremost is the six-month tour which stretched into a year; then there was the time that a Japanese submarine sank the ship which was carrying the entire supply of beer and other essentials for the base; and a Medical Officer who was ‘as mad as a hatter’ who, amongst other things, would jokingly test the engines of the Blenheims with his stethoscope; and the inevitable meal as the guest of the Sheikh of Sharjah. Ben, who was at this time the WOp/AG to the CO – Wg Cdr Gyll-Murray – relates the tale:

‘I remember the CO and I were sitting next to each other, cross-legged on the floor, with a mountain of rice in front of us – the main dish being goat. It is customary for the host to eat one eye of the goat, and the chief guest the other. The CO said he didn’t know how he was going to do this, so I suggested he surround the eye with rice and swallow it. This he did.’

On 23rd August 1942, Ben’s pilot of 21 Squadron days, Freddie Reiss, who was still at No 70 OTU Nakuru, had a fatal motoring accident. Freddie had hit a tree, and was rushed to No 2 General Hospital but died later that day as result of his injuries. He was buried in Forest Road Cemetery, Nairobi.

At the end of March 1943, Ben returned to Egypt, this time to join the staff of No 75 OTU, Gianaclis (Alexandria). Ben described this place as a sort of transit camp. Ten months later, he made a three-week guest appearance with 55 Squadron, Kabrit (later Kibrit, 20 miles north of Suez), before returning by boat to the UK, docking at Liverpool. After three weeks disembarkation leave, Ben was posted to No 1 Radio School, Cranwell, for a W/T refresher course, arriving on 14th April 1944. This holding manoeuvre lasted five weeks, after which Ben was posted onto Wellingtons at No 105 OTU, Bramcote, Warwickshire. ‘They were selecting certain crews to form Transport Command’, Ben explains, ‘and our job was to keep the airways open for British airlines.’

In January 1945, Ben joined No 11 Ferry Unit, Talbenny, Pembrokeshire. Shortly after his arrival, he converted from Wellingtons to the ubiquitous Dakotas. Ben was by now the proud possessor of a certificate to say that he was qualified to be a wireless operator on any civil aircraft; ‘Not that I took it up’, he added.

After the passing of VE Day, Ben then went to No 108 (T) OTU, Wymeswold, before joining 187 Squadron at Membury, near Hungerford, One of his jobs on the squadron was to fly troops back from India on what they called ‘python leave’.

In May 1947, Ben was posted to the East African Communications Flight, Nairobi, for VIP duties: a tour which he described as the most pleasant of his RAF career, though hastening to add that he enjoyed it all. Life is never without problems. Whilst there, Ben was promoted to squadron leader, and because he now outranked his pilot it was considered bad form, and he was told that he would have to return to the UK. With Vera and young daughter Jenny already on the boat to join him, Ben was none too happy. Help came in the nick of time, when Montgomery arranged a visit to the East African troops, and Ben was given a last-minute reprieve. Ben warmly recalls:

‘Our main job on that VIP crew was to fly the AOC, the GOC and the Governor of Kenya; they were the only three that we used to fly around. A lovely job because wherever we went, we were invited wherever they were going!’

It was not all a bed of roses, however: the first time that they flew the GOC (Maj-Gen William Alfred Dimoline CB CMG CBE DSO MC), in a Dakota on a visit to Madagascar, was one of those sorties that the crew would have liked to forget, as Ben confesses:

‘I’ll tell you what happened. We were showing the flag to commemorate the Battle of Britain; there were visiting Spitfires and we had a Guard of Honour, which I was in charge of, each time we landed. And at Madagascar we came in a bit too low, and I felt the bump: the undercarriage was obviously fractured. As soon as we sat down, we really sat down, and the whole thing collapsed. We slithered along the runway – how embarrassing! We were all supposed to be pretty hot stuff in each category of pilot, navigator and wireless operator, you see, as Transport Command. I remember looking back, and there was poor old “Dimmie”, covered in suitcases up to here – and he was grinning! He was a wonderful man, he really was.’

Many years later, by one of life’s strange coincidences, daughter Jenny was recommended to school the horse belonging to none other than Dimmie’s brother, Brigadier Harry Kenneth Dimoline CBE MBE DSO TD CPM. Naturally a reunion was swiftly arranged. The GOC had a good memory, and immediately reminded Ben that he had pranged him on his first trip!

The VIP crew were occasionally required to carry visiting dignitaries, such as MRAF Sir John Salmond GCB KCB CMG CVO DSO & Bar on 19th September 1947. All good things come to an end, and by the close of the year, Ben and his family were homeward bound on SS Matiana.

The start of a dull life? Not quite. Ben soon found himself in the hot seat of SATCO at Gatow Airport during the Berlin Air Lift. This post brought him into contact with AVM Don Bennett CB CBE DSO. The retired Pathfinder boss was none too pleased when Ben was forced to close the airfield on one occasion, due to fog – it was costing him a lot of money to have his Tudors grounded! Strangely enough, their paths were to cross yet again, some years later, when Don Bennett wished to extend Blackbushe Airport over some adjacent common land. A conflict of interests arose on account of the fact that the land had long been in use by equestrians, including Jenny, for the exercise of their horses…(For further Don Bennett memories, see Tom Jefferson’s biography).

After Gatow, where Ben’s next door neighbour was Rudolph Hess (he never met him), it was back to the UK again. Signals Leader posts at HQ 3 Group, Bomber Command, Bawtry Hall, and then HQ Transport Command, Bushey Park took care of the next two years.

Two entries, as a passenger, in Ben’s logbook clearly reveal the arduous tasks he was required to perform during his sojourn with Transport Command:

’15th October 1950: BOAC Argonaut: To Singapore with team of officers from Transport Command and Air Ministry to prove route (radio facilities) for Vampires: London – Cyprus – Bahrain (Persian Gulf) – Bombay – Colombo – Tengah. Total: 35.00.

24th October 1950: Dakota: Changi – Butterworth (Malaya) – Bangkok (Siam) – Rangoon (Burma) – Calcutta – Delhi – Karachi – Sharjah (Arabia) – Bahrain (Persian Gulf) – Habbaniya (Iraq) – Mafraq (Trans-Jordan) – Fayid (Egypt) – El Adem – Malta – Istres – Oakington 7th November 1950. Total: 56.00′. Can’t be bad!

At the end of the year, Ben was posted to No 3 RS at Compton Bassett to command a signallers’ wing, tasked with the training of national servicemen. Just over 2½ years later, he was on the move again; this time, to No 2 ASS (Air Signals School) Halfpenny Green, in the capacity of CGI for signals. Eight months later, Ben commenced what was to prove his last posting in the RAF, that of Chief Air Instructor (Signals) at No 1 ASS, Swanton Morley. His last recorded entry in his logbook is for 29th June 1953, in an Avro Anson, tasked with ‘Air Signaller Cadet Training’. One year later, Ben’s first biographer – at that time, a fresh-faced ATC cadet – excitedly climbed aboard an Avro Anson for his very first flight.

Ben was invalided out of the RAF on Christmas day 1954, owing to a perforated eardrum. Following a three-month resettlement course at Balham and Tooting College of Commerce, he chose another radio-orientated job, and took employment with McMichael Radio of Slough on MOD contract work. Nineteen years later, Ben had become assistant to the works director and opted for retirement at the age of 60. He was released one year later, after a suitable replacement had been found, and has enjoyed retirement ever since. He is a keen bird-watcher (RSPB member) and a dedicated bowls enthusiast, with dual allegiance to the Cirencester Bowling Club (Life Member) and the élite Cotswold Strollers Bowling Club.

A modest man, Ben declared that he only reached officer rank ‘because people were being bumped off so quickly’. He does concede, however, that he has probably not done too badly considering his foreshortened elementary school education. Thumbing through Ben’s logbooks, with ‘Above the Average’ and ‘A’ Category assessments, I would tend to agree with that!

I asked Ben if he could provide me with a few more details concerning his ‘Rotterdam’ crew. ‘Freddie Reiss was from a very wealthy family in Argentina’, he replied, ‘and must have been in cattle farming.’ And he remembers well those happy days visiting the Samson and Hercules dance hall (later Ritzy’s Night Club) in Norwich, in Freddie’s lovely white Packard.

Ben was pleased to hear that Edmund Shewell had also survived the war, as a squadron leader. ‘He was rather quiet’, Ben recalls, ‘and studious, I would say. Not one for parties, or anything like that. He was my height (5’8″), I should say, and had fairish hair.’

Our long-overdue interview had been well worth waiting for. But I had just one complaint, concerning Ben’s membership of the Royal Air Forces Association. ‘Why ever didn’t you place an advert in our magazine, Air Mail. Rusty?’ Ben asked me. I did – in the Help section of the Winter 1981 issue . . .