This biography was authored by Rusty Russell and has been extracted from Mast High Over Rotterdam – Please respect Rusty’s Copyright to the work as detailed in the first section of the book.

In March 1984, a letter from Switzerland was pushed through my letterbox. Full of curiosity, I opened it. To my surprise and delight, it was from Canadian-born Bob Carey, who had found the lifestyle and culture of the European continent vastly preferable to that of the continent of his origins. Frank Campbell-Rogers had kindly informed Bob of my research project.

Bob was to prove not only a valuable source of information for this book, but also a very good friend. The writing of his biography is not so much a search for information but more a question of how best to précis the wealth of information available to me, yet still portray the essence of my friend.

Bob’s contribution to this book will have already been noted; but what sort of life has he led? To have survived any length of time on Battles in the AASF and Blenheims in 2 Group, there is only one answer – lucky!

Born in Goderich, Ontario, in December 1921, Bob realised that if it was adventure he wanted, the last place to be in 1938 was the wrong side of the Atlantic. Accordingly, he joined the RAF as a Boy Entrant u/t Wireless Operator in September of that year. After training at No 1 E&WS, Cranwell, Bob was posted as a wireless operator to the Sector Operations Centre at RAF Turnhouse in Scotland (now Edinburgh Airport), just in time for the outbreak of war. Curiously, Bob described his work as a sector controller as the most interesting part of his RAF service, as he was in constant touch with the fighter pilots as they were vectored onto any bomber in the vicinity. Curious, because everybody knows how boring fighter pilots can be, and no one else that I have ever met has enthused about being ‘sent down the hole’.

By the end of the year, Bob was experiencing that well-known urge, and remustered to aircrew. After a course at No 9 B&GS, Penrhos in Wales, Bob joined No 12 OTU, Benson, as a fully qualified WOp/AG in April 1940. On 1st June, Bob was posted to 226 Squadron in France, at a hectic time for the AASF.

Memory is strange: it seems to hold on to the good and hilarious times and discard the poignant. Bob’s is no exception. He vividly recalls an incident during the dark days of the war:

‘The rate of exchange in France in 1940 for the £ Sterling was 240F to the pound. As young AC1 WOp/AGs, our basic pay was ten bob [50p] a week plus one and six [7½p] per day risk allowance – about £1 a week or 240 French Francs. I mention this to illustrate the discrepancy between the pay of the French soldiers (14F per week) and ourselves; consequently, we were somewhat in the position of the Yanks in the UK in ’43 versus the RAF, paywise.

The commandeered farmers’ fields we were using as an advanced airfield in May and June of ’40 were near the single street village of Suzé, a village that boasted two or three earthen-floored wine cellars, generally equipped with long tables and benches. Off duty we would frequent one or all of these Bistros.

On the afternoon in question, I was with Bob Beal [Jock Paton’s WOp/AG on the Rotterdam raid]; wearing our 38s etc, we occupied the only two-place table in the Bistro. When we realised that a bottle of Champagne cost only 14/15 Francs (a week’s pay for the Poilus), we ordered a bottle each and began (under the bemused stares of 20/25 Poilus sitting at the long tables and drinking 20/30-centime glasses of vin du pays) with a disgusting display of bravado, wealth, and tactlessness (the French army was in full retreat) to consume both bottles.

An hour or so later, the peace was shattered by a low-flying, machine-gunning Dornier 17, the first of five or six passing over the village to bomb the dispersed Fairey Battles. (This happened two or three times a week). The half-inebriated RAF types rushed outside and began firing their 38s at the Dorniers, which were making repeated passes, and at the local building chimney pots. I don’t know where Bob Beal got to, but I nipped around the corner of the Bistro, and with drawn revolver, Champagne and glass, ran up a ladder, whose end protruded several feet over the apex of the roof of a nearby barn. A Do was passing 50/60 feet directly overhead. I could clearly see the air-gunners, so I fired away as it passed on to the airfield. Suddenly, I heard and felt, almost simultaneously, the roar of a Do’s engines, machine guns, and bullets striking the barn just to the right of the ladder. I remember vaguely gripping the sides of the ladder with my elbows, removing feet from the rung, and making a rapid and more or less controlled descent. Landing on my back, and with gun, Champagne and glass intact, I was almost instantly grabbed by the ankles and dragged, dazed and bruised, across the yard and down the steps leading to the cave of the Bistro, by a young engine mechanic (whom I knew), who had taken shelter there. We finished the bottle together.’

By mid-June, the squadron had begun the hasty retreat from France. Ground personnel did a swift exit-stage-left towards Rennes, vividly recorded in the squadron ORB, while the fly-boys pointed their machines in the general direction of England. Bob’s Battle made a slight detour by way of the island of Guernsey, for understandable reasons.

It all started in August 1939, when Bob took some leave to visit Guernsey, where his grandfather had lived before emigrating to Canada in 1850. There, Bob met and fell in love with Georgette Rufenacht, a young lady born in Belgium of Swiss parentage, and domiciled in Guernsey for some three years. Bob clearly remembers the feeling of anguish as he overflew his fiancée, with a strong temptation to bale out and go to her assistance. But Georgy was made of the right stuff and managed to leave on the last boat out of Guernsey before the Nazi occupation at the end of the month. Bob added:

‘One amusing coincidence [was that] my aunt in Victoria B.C. met an old friend in downtown Victoria (in the summer of 1940) whose husband was the Belgian Consul in Victoria, and during the ensuing conversation, mentioned that her nephew was in France, that they were worried and had not had news for some time. Mrs Gekman commiserated, and said that her husband’s sister’s daughter had managed to escape on the last boat from Guernsey to England, and that they too were concerned. Was her name by any chance Georgette Rufenacht? A small world!’

Meanwhile, the situation aboard Bob’s battle was critical. With no navigational equipment, no ammunition, and very little fuel (not helped by the detour!), the Battle crossed the Channel at wave-top height, just reaching Brighton before having to force-land. The crew’s appearance was so dishevelled that they were assumed to be deserters, and incarcerated in jail overnight. The next day, after identification, the famous British hospitality was restored.

Now based in Belfast and carrying out anti-submarine patrols – perhaps the safest employment for the obsolete Battles – Bob took the plunge, and married Georgy in London in January 1941.

Bob well remembers one particular incident during his last days on Battles, which nearly caused a curtailment of his career. Bob, in fact, owes his life to Ginger Morgan, Daddy Kercher’s observer before he loaned him with tragic consequences. What happened was that Daddy Kercher bunted the aircraft, normally a safe enough manoeuvre if the chain from the floor of the Battle is attached to a clip near the crotch of the air-gunner’s harness. But Bob’s was not attached, and the ensuing negative ‘g’ caused him to leave the aircraft, minus parachute! Ginger just caught Bob by the ankles and prevented him from going any further.

In June 1941, Bob was in 2 Group, based at Wattisham, operating Blenheims. As if there was not enough carnage on operations, Bob remembers several horrific accidents when the Blenheims were on training flights. One such occurrence took place after Bob had been posted to 21 Squadron (23rd July 1941). Wg Cdr Kercher was leading a vic of three, when his No 2 suffered an engine failure on take-off, rolling over onto its back and hitting the No 3, crashing together. Wg Cdr Kercher hurriedly came round, slapping his Blenheim onto the ground and causing his port undercarriage to collapse. He and his crew rushed over to try and render assistance, but both aircraft were ablaze by then and the crew were beaten back by the flames. To make matters worse, the fire-tender arrived and when the valve was turned on, no foam emerged. One of the air-gunners had been a good friend of Bob’s, and the suffering of those poor crews is something that he can never forget. Fate is not discerning – both crews were very experienced. Referring to W.R. Chorley’s Royal Air Force BOMBER COMMAND LOSSES of the Second World War 1941, this would appear to be the collision that occurred on 28th July 1941, at Swanton Morley, between 21 Sqn’s Blenheim Mk IV, P6954, and 88 Sqn’s Blenheim Mk I, L1342.

For his contribution to the raid on the Fortuna Power Station at Quadrath, Cologne, on 12th August 1941, Wg Cdr Kercher recommended Bob for the award of the DFM. Due to an administrative cock-up, Bob never received his ‘gong’. When Bob visited the Kerchers in Hitchin after the war, the wing commander confessed that he was sorry to this day that he had never followed it up. Such are the fortunes of war and their rewards.

During a detachment to Lossiemouth in September 1941, Bob had two memorable experiences. The first occurred after an evening out at Elgin, when Bob was trying to make his way back to Lossiemouth. When he was about five miles from Elgin, he saw an aircraft coming in to land, and then he spotted a parked Wellington and a sentry. The sentry-box had a rifle and bayonet propped up outside it, while the sentry was having a pee. Bob picked up the rifle and went over to the sentry and said: ‘Excuse me, but is this yours?’ The sentry was grateful. Bob continued: ‘Do you know where the Blenheims are parked?’ The sentry disconcertedly replied: ‘What Blenheims?’ Bob said: ‘Oh my God, isn’t this Lossiemouth?’ ‘No!’ was the reply, ‘It’s Kinloss – you’re the wrong side of Elgin: you’ve got another ten miles to go!’ So poor old Bob hiked back to Elgin, and having had just about enough by the time he got there, sat down on the steps of a building. The sound of heavy footsteps approaching, stopping, and then mounting the steps: it was a policeman. Bob explained his predicament. The policeman replied: ‘Look, if you keep quiet, I’ll put you in a cell, but I’ve got to lock it up if you don’t mind. Don’t tell the Sergeant or I’ll really be in it!’ Bob was quite happy with the arrangements. In the morning, when he was ‘released’, he was taken to Lossiemouth and was at briefing before anyone else.

The other memorable experience followed a session when Bob was trying to clear his guns of stoppages, of the worst kind – when one shell is pushed up the case of another. Using a special tool to bore them out, Bob was getting absolutely filthy, when Bryn Evans suddenly shouted to him: ‘Hey! The AOC’s coming with the Station Commander!’ They informed Wg Cdr Kercher, and the three of them, all filthy, came smartly to attention outside their aircraft. The AOC said: ‘Sergeant Carey?’ ‘Sah!’, Bob fired back. AOC: ‘Have you just been on operations?’ Bob: ‘Yes, sir!’ AOC: ‘See any enemy aircraft?’ Bob: ‘Yes, sir!’ AOC: ‘Did you have any hits?’ Bob: ‘Don’t know, sir!’ The AOC turned round to the Station Commander and said, in a leg-pulling tone of voice: ‘What sort of air-gunners have you got, who don’t know if they’ve hit enemy aircraft?’ Then, out of the blue, he said to Bob: ‘Well, Sergeant Carey, how would you like your commission?’ Bob, dumbfounded, did not know what to say. Wg Cdr Kercher, for the only time in his life, got annoyed, and said to Bob: ‘Sergeant Carey – answer the AOC!’ Bob meekly replied: ‘Er, thank you sir!’ About two months later, the commission came through.

Not all encounters with German fighters were unpleasant. Bob remembers a time when they were attacking a target in two vics of three Blenheims apiece, and they passed six Messerschmitt Bf 110s going in the opposite direction, but about 800 yards away and just outside effective gun range. Neither of the formations fired: they just looked at each other. They were both on their way to their respective targets. After the war, Bob actually met one of the Bf 110 pilots: they compared their logbooks and realised that they had passed each other!

The start of his commissioned service coincided with the end of Bob’s operational flying. A succession of instructional tours at various gunnery and armament schools and OTUs must have nearly finished him off by the time the end of the war loomed up. In March 1945, on a whim, he transferred to the RCAF; a decision, he candidly admits, he has regretted ever since, wishing that he had stayed in the RAF.

For much of Bob’s RCAF service he was concerned with the development of ECM, and was once again employed as an instructor. In 1963, the RCAF dangled the usual carrot in front of him: ‘If you stay in, you’ll get Squadron Leader!’ Bob elected, instead, to accept their offer to stay on in a civilian capacity in Metz, retiring to Switzerland one year later.

Since then, Bob has managed a caravan site near his home, and his wife Georgy has run a small boutique.

The hospitality lavished upon us by the Careys, when my wife and I met them at their charming home in Switzerland, in October 1984, was overwhelming. It was also a memorable experience in other ways. Evenings often stretched into the early hours of the morning to the strains of German marching songs, and Bob’s no mean rendering on his harmonica. To be honest, we were somewhat surprised at Bob’s obsessional admiration for the German war effort, particularly concerning the Waffen SS. Great fighters, certainly, but Bob seems to have forgotten Oradour-sur-Glane and the dreadful extermination camps.

One understandable legacy of the war years, which we discovered from his daughter Chris, is that Bob will not go near an aircraft now, and will not allow any of his family to fly either.

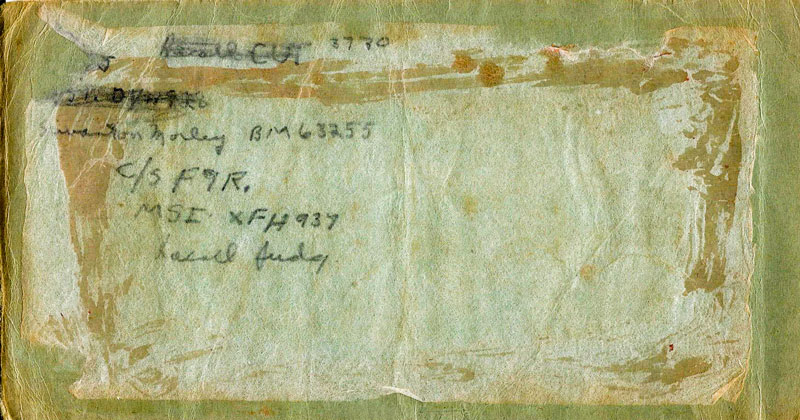

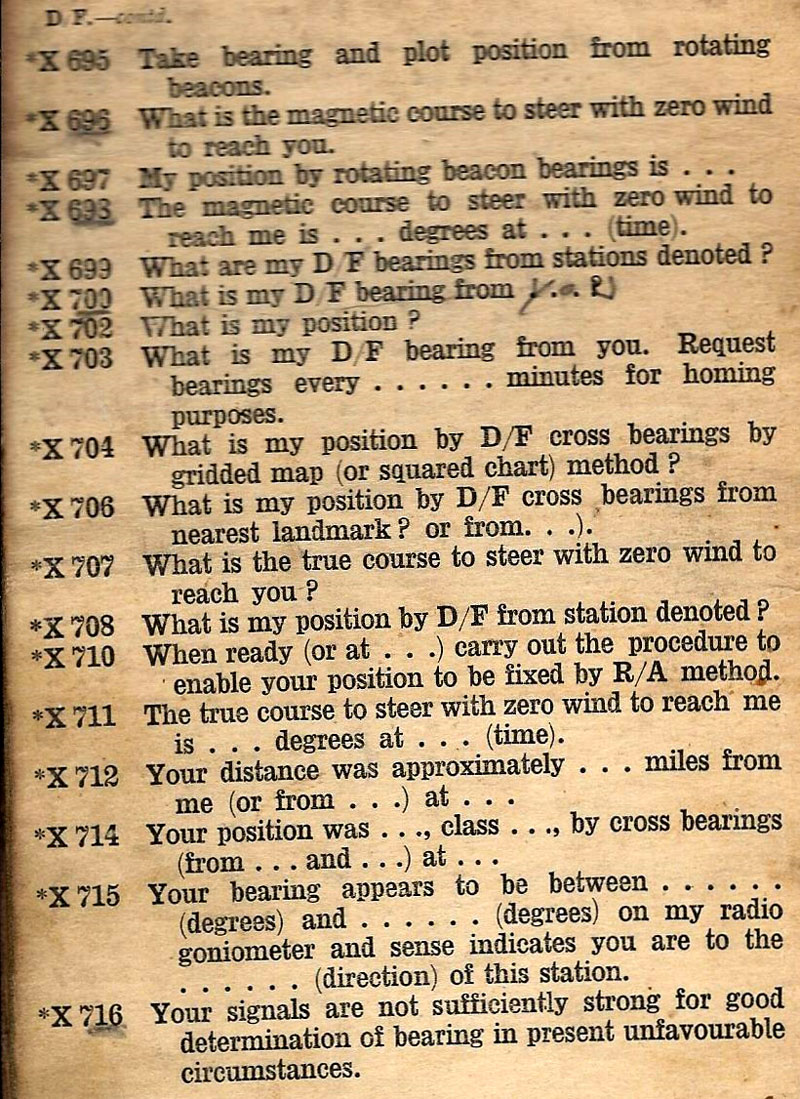

At the end of our stay, Bob presented me with his signals book. On the left-hand page, composed of rice-paper, would be written the latest orders: this has the recall codeword JUDY inscribed. Bob reckons that he still had possession of it because the authorities forgot to collect them after the recall. Bob also gave me his AIR PUBLICATION 982: AIRCRAFT W/T OPERATING SIGNALS 1939. Perusing the list of X Codes, I would guess that X703 (What is my D/F bearing from you? Request bearings every …… minutes for homing purposes) would be the most popular, with X707 (What is the true course to steer with zero wind to reach you?) coming a close second! These books are some of my most treasured possessions.

Hi , where did you purchase it ? I would be interested in getting one.

Hi Carla,

I just came across this site while conducting various searches of Bob (and Georgette) Carey, who I believe from your message back in 2018 is your grandfather. My father, who passed away in 2016, Phil Carey, was your grandfather’s cousin and had visited him in Switzerland but had lost touch. I believe from the family tree that I was passed down after the passing of my parents that your grandfather had two children, Christine Marlene and Robert Phillip George. I am looking for further information for the family tree – to update it and verify its accuracy – and am wondering if you’d be willing to reach out to me at smcareyover@gmail.com?

Thank you so much,

Stuart Carey

Hello, I have just bought a 1960 photo album full of photos of bob Carey on ski exercises in Bavaria and austria

It’s lovely to read some history from my grandpas life. Thank you