At 0755 on February 18th. 1941 a Heinkel HE111 H3 of 4/KG 53, The Condor Legion, Work No. 3349 attacked RAF Watton from the South side of the airfield travelling North. The aircraft strafed the airfield, hangar line and technical site and then flew into the forest of cables that had been sent up by Parachute and Cable defence system. The aircraft was so damaged by this that it came down about 1.5 miles North of the camp at Ovington.

Local historian, Robin Brown, in an article in Saham Saga around 2000, told how the crew – Pilot; Feldwebel Heinrich Busch under the command of of Oberleutnant Erich Langrach, with Unteroffizier Werner Schmoll as radio operator and two others as air gunners were based at Lille in occupied France; they had been ordered to attack a convoy in the mouth of the Wash at dawn.

After one change of aircraft due to unserviceability, more bad luck befell them when shortly after the start of the mission the replacement aircraft’s radio and radio compass became unserviceable. In these circumstances they should have returned to base but decided to carry on. This was a bad decision as there was a lot of cloud, most of it down to ground level and very little chance of seeing where they were.

Navigating by gyro compass and dead reckoning they flew until they supposed they were over the Wash but still there was no break in the cloud so, at about 7 o’clock, they decided to return to base. They altered course for Lille, steering 120 degrees and flying at about 3,000 feet, When they estimated they were over Belgium they descended to 900 feet and broke cloud and saw the coast ahead. Unfortunately this was the coast of Norfolk, not Occupied Europe, a fact they soon realised when an unfamiliar landscape appeared and anti-aircraft guns started firing at them. The rest, as they say, is history.

The Parachute and Cable system took the form of green boxes about 2 feet square placed on stilts about 2 feet above the ground arranged in lines with 60ft between each. The boxes contained a rocket, known by locals somewhat disparagingly as “Fizzing Onions”, and fired a 480ft length of steel cable to 600ft height in the path of any low flying aircraft.

Once at the correct height a parachute would open open slowing the descent of the cable so that it effectively ‘hung in the air’ for some time hoping enemy aircraft would fly into the forest of cables, when the increased drag on the aircraft would put the aircraft out of control.

The whole system was fired electrically from Gunpost “F Freddy” located just behind what is now the Aerolite Garage. It was said locally that a thunderstorm in the vicinity would often result in random firing of the rockets causing quite some spectacular displays.

First hand accounts have told us that the gunpost crew were having breakfast on the roof that morning when the Heinkel attacked and it was only in their hurry to get out of the way of the shooting and under the cover afforded by the post, that the firing button was accidentally pressed!! As far as we know this is the only aircraft to have been brought down by the Parachute and Cable system in East Anglia.

The crew of 5 were taken prisoner by Dudley Bowes and Frank Warnes using a shotgun and pitchfork. Gerald Warnes, son of Frank, has traced the story through newspaper archives of the time. This is how Mr Dudly Bowes related the story to an EDP reporter:

“It happened in the morning as I was getting my breakfast when I heard a shrieking noise of aircraft and saw a German bomber coming down in one of my wheat fields.

“I ran out towards it carrying my 12 bore gun, and called to those of my men who could hear me to follow. Warnes was soon on my heels. We went across one field and then through a hedge into the wheatfield where we saw the German plane, the crew of which had tried to set it on fire. Their ages ranged from about 21 to 30, and one of them, not the pilot, was wearing an Iron Cross.

“The pilot was a man of about 25. The other men had taken off their parachutes and these were lying on the ground. Warnes and I got near and I fired my gun into the air. That stopped them doing anything but throwing their arms up.

“They surrounded to Warnes and me and then my wife and boys came on the scene. She had heard my 12 bore fired and was afraid it was the Germans firing at me. As I left the house, she had, however, acted immediately on the request I made for her to telephone the police and s we waited for the authorities to take control of the situation.

“Two of the crew could speak English and they told me they had come from a French aerodrome and had hoped to return to it. They still had some incendiary bombs on the plane and said they had dropped high explosives a short time before.

“The rear gunner had bullet wounds on the face and a bullett had ripped through the shoulder of the pilot’s tunic and scraped the flesh which was bleeding. These were the only injuries the men had suffered.

“I drove three of the Germans and a Policeman to the Police-station and the sergeant and the other constable took the other two.”

Mr bowes also said that while they were waiting for the Police to arrive he had a chat with the two Germans who could speak English. One, who could speak it quite well, said he had learned it at school. They seemed honestly to believe that Germany would win the war and said that, like our ‘boys’ they were only fighting for their country.

Mr Bowes said “I offered them a cigarette each and while they accepted they asked me to have one of theirs. They had a generous supply of Turkish, but I told them to keep them as they might want them and anyhow it would be a treat for them to smoke an English one. And evidently it was”

For their bravery in apprehending the crew, Bowes and Warne received recognition from the King, and in June 1941 the following notice appeared in the London Gazette:-

CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD

St. James’s Palace, S.W.1, 13th June, 1941.

The King has been graciously pleased to give orders for the publication in the London Gazette of the names of the persons specially shown below as having received an expression of Commendation for their brave conduct:-

For services when an enemy aircraft crashed and the crew were taken into custody.

George Dudley Bowes, Farmer, Norfolk.

Frank Wilfred Warnes, Farm Labourer, Norfolk.

The two senior officers from the crew were taken to RAF Watton’s SHQ where they were met by the CO. The CO’s secretary, Audrey Ranyard, at one of the reunions in 1989, remembered their arrival at Watton. “One of the men was very tall and stern looking” she said, “I was quite frightened of him”

“They were taken into the CO’s office and were offered tea and some cake. They were quite shocked at this and made it clear they had been told that Britain was on its knees with no food. It was odd seeing their reaction when they discovered what they had been told was false.”

Local man, Ronnie Thompson, has also added his memories of the day. Ronnie was going to work on the morning of the incident behind Westmere House on Lord Walsingham’s estate. They were just opening a five bar gate when all around them was tracer fire hitting the ground which Ronnie thinks came from the RAF station firing at the Heinkel. How they weren’t hit he didn’t know because it was all around him.

They heard that the aircraft had been brought down and at 4pm he rushed over to Ovington to look at the aircraft but the soldiers guarding it wouldn’t let him near it. Although during the day they had been letting people close it and even sit in the cockpit but bits were being lost to souvenir hunters. The following Sunday Ronnie was out on his bike and cycling along and a despatch rider stopped him and told him to get off the road. Two Queen Mary’s (large lorries) came along with the aircraft on board, the first with fuselage and second with wings and engines (on its way to Farnborough).

The Despatch rider gave him a Jubilee Clip marked BRU GERMANY – now lost. Sometime later Ronnie was in Watton and a Heinkel 111 painted all yellow passed low overhead as if it had just taken off from airfield – he is sure that was the Ovington A/C brought back here to teach aircraft recognition.

All of the crew eventually found themsleves POW in Canada but the for one, the Pilot Heinrich Busch, the story does not end as you might expect.

The following is extracted from the Edmonton Journal where you can read the full story

In 1944, like other prisoner of war camps in Canada, Medicine Hat camp No. 132 had its own internal police force, its own hierarchies and government, its own systems of discipline. Though the camp was guarded on the outside by Canadian soldiers, daily life inside the wire was entirely dictated by the German inmates themselves.

After an attempt was made on Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s life that July at his field headquarters in East Prussia, rumours circulated that a revolutionary movement was planning to take over the Medicine Hat camp by force. Canada’s highest-ranking prisoner of war decreed from Ontario that anyone suspected of traitorous activities against the German Army was to be identified and killed in a way that looked like a suicide. One of those suspected traitors was fellow prisoner Karl Lehmann.

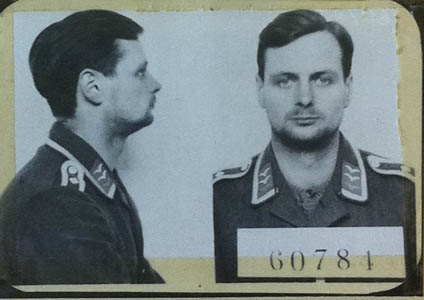

At the Medicine Hat camp, four prisoners started making a plan. They were: Willi Mueller, a pilot who had made 78 trips over enemy territory before being shot down and captured by Allied troops north of Glasgow in May 1941; Heinrich Busch, who had been shot down in England early in 1941; Bruno Perzonowski, a navigator who was captured in North Wales; and Walter Wolf, a sergeant who had been captured in North Africa and brought to Canada as a prisoner of war in 1942.

Watching Lehmann walk across the yard one day, Wolf turned to a friend. “Whenever I see the fat one, I see a rope around his neck,” he said.

Before the war, Lehmann had been a respected academic, a professor of languages who taught at the University of Erlangen. The quiet, heavy-set German had first been suspected of revolutionary activity while being held at a PoW camp in England, and was now thought to be the leader of the suspected uprising in the Medicine Hat camp.

On the evening of Sept. 10, 1944, Mueller, Busch, Perzonowski and Wolf asked Lehmann into one of the huts, saying they needed his help them with some papers.

Once inside, they ushered him to a bench. “Do you know anything about the communistic activities in the camp?” they asked.

When Lehmann said no, they beat him and slipped the noose around his neck. The men left Lehmann dead at the end of the thin rope, his face swollen and battered, his knees bent, feet dragging on the floor.

On December 18th 1946, for his part in this crime, 29 year old Heinrich Busch, pilot of the aircraft shot down at Ovington, was hanged at Provincial Gaol, Lethbridge in Canada.

My grandad, Ron Graves, was one of the PAR crew that fetched it down.

I am Gerald Warnes, the eldest son of Frank Warnes, but remember nothing of what happened on that day when my father, with his boss Dudley Bowes dealt with those Germans as I was just 22 days short of my second birthday at the time.

As the article mentions, my knowledge of what happened has been gained from Newspaper archives, as unfortunately my father spoke little off it and nothing remains of the documents and other paraphernalia he received from the King at the time.

My Father remained in Dudley’s employment until 1953, and we occupied one of the four Hill Cottages (now demolished) on the main Dereham Road.

We moved from there to live at Wolterton, where my father took employment with Lord and Lady Walpole as a herdsman remaining there until he retired. He died in October 2013.

I married and eventually moved to Dersingham in West Norfolk, (sadly now a widower) where doubtless I shall remain.

Hi Gerald – I trust all is well with you. JUlian

I was only 6 months old at the time of the crash. I recall my mother telling me about it, as the aircraft crashed behind our house (Invivta Cottages, Ovington)

She said she went to look at it, carrying me in her arms. Told me the crew were rounded up, with someone with a shotgun. Thanks to the above info, I now know it was Dudley Bowes, he later owned the slaughterhouse in Brandon Rd, Watson.